Event Sourcing Examined Part 3 Of 3

In this 3 part series we will look at what event sourcing is and why enterprise software for many established industries use this pattern.

Index

- Part One

- Introduction to Event Sourcing

- Why Use Event Sourcing?

- Some Common Pitfalls

- Part Two

- Getting Familiar With Aggregates

- Event Sourcing Workflow

- Commands

- Domain Event

- Internal Event Handler

- Repository

- Storage & Snapshots

- Event Publisher

- Part Three (This one)

- CQRS

- Read Side of CQRS

- Using NEventLite

Event Sourcing as demonstrated in the previous blog posts is a GREAT way to implement the command side of CQRS. In this post, we will be looking at how to implement the read of CQRS and using my event sourcing “framework” NEventLite.

CQRS

Command Query Responsibility Segregation is an idea where we can model our solution to have separate write and read models. The idea was championed by Greg Young in the mid 2000s and since been adopted by many. It has its roots in CQS (Command Query Separation).

CQRS is hard to implement properly but has a lot of advantages like scalability for performance critical applications. As most information systems have magnitudes more reads than writes it makes more sense to have separate models to cater for specific concerns of read and write.

Have a look at Martin Fowler’s explanation here.

Read Side of CQRS

In the event sourcing methodology all we persist are domain events. If we don’t have a separate read model/view we would have to read all the past events to do an aggregation or to find a count. This is bad. Remember how CQRS dictates different models for write and read? Good. You can probably see where I’m going with this now. What we need is an optimised read-only model/view.

In the example of the Purchase Order we might want to show the customer previous purchase orders and the totals. Also, a warehouse manager might want to see the products and orders pending. Part of DDD is to identify these needs. One approach I’ve used is to create a separate read model for each page/grid/widget. This allows us to reuse views more often.

These read side event handlers then subscribe to domain events and updates read models as necessary. The update logic is self-contained and isolated from other views. This means we can have as many views as we like listening to domain event broadcasts. This gives us the ability to scale different views as required. (When I use the word view here I am talking about the read model + the event handler)

Let’s look at the sequence of events.

At start up,

- PurchaseOrderSummaryView subscribes to PurchaseOrderCreated, Updated events

- ProductOrderSummaryView subscribes to PurchaseOrderItemAdded, Updated events When customer places an order,

- Domain event created

- Persisted to the event store (Artefact of the command side)

- Broadcasted to the message queue

- External Event handler receives an event (message) it subscribed to (I use the term internal event handler to describe the event handler inside the AggregateRoot)

- External Event handler reads the message and updates the read modelto reflect the changes.

- Optionally: Persist the last event version to the view as we can later use this to determine the “freshness” of the view.

Using NEventLite

NEventLite is a lightweight library I created to do the mundane tasks associated with setting up an event sourced system in .net. Think of it as event sourcing on rails.

We are going to look at the examples provided in my github repo. We have very small project that demonstrates use of ES with snapshots and a read model.

Look at the sample Note domain model.

public class Note : AggregateRoot, ISnapshottable

{

public DateTime CreatedDate { get; private set; }

public string Title { get; private set; }

public string Description { get; private set; }

public string Category { get; private set; }

#region "Constructor and Methods"

public Note()

{

//Important: Aggregate roots must have a parameterless constructor

//to make it easier to construct from scratch.

//The very first event in an aggregate is the creation event

//which will be applied to an empty object created via this constructor

}

//The following method are how external command interact with our aggregate

//A command will result in following methods being executed and resulting events will be fired

public Note(Guid id, string title, string desc, string cat):this()

{

//Pattern: Create the event and call ApplyEvent(Event)

ApplyEvent(new NoteCreatedEvent(id, CurrentVersion, title, desc, cat, DateTime.Now));

}

public void ChangeTitle(string newTitle)

{

//Pattern: Create the event and call ApplyEvent(Event)

if (this.Title != newTitle)

{

ApplyEvent(new NoteTitleChangedEvent(Id, CurrentVersion, newTitle));

}

}

//... see github repo example sample for full source code

As you can see we are following the pattern of creating an event and applying it. The internal event handlers are marked with a custom attribute and some “reflection magic” by the framework knows to call the right one when the ApplyEvent method is called.

[InternalEventHandler]

public void OnNoteCreated(NoteCreatedEvent @event)

{

CreatedDate = @event.CreatedTime;

Title = @event.Title;

Description = @event.Desc;

Category = @event.Cat;

}

[InternalEventHandler]

public void OnTitleChanged(NoteTitleChangedEvent @event)

{

Title = @event.Title;

}

The Note class also implements ISnapshottable which adds these two methods allowing it to re-hydrate itself faster. (See part 2 of the blog series) .

public NEventLite.Snapshot.Snapshot TakeSnapshot()

{

//This method returns a snapshot which will be used to reconstruct the state

return new NoteSnapshot(Guid.NewGuid(),

Id,

CurrentVersion,

CreatedDate,

Title,

Description,

Category);

}

public void ApplySnapshot(NEventLite.Snapshot.Snapshot snapshot)

{

//Important: State changes are done here.

//Make sure you set the CurrentVersion and LastCommittedVersions here too

NoteSnapshot item = (NoteSnapshot)snapshot;

Id = item.AggregateId;

CurrentVersion = item.Version;

LastCommittedVersion = item.Version;

CreatedDate = item.CreatedDate;

Title = item.Title;

Description = item.Description;

Category = item.Category;

}

Once the framework applies the event, it publishes the event using the IEventPublisher. In the example I’m using an in-memory subscriber and injecting it in. (This isn’t how you would use it in production)

public class MyEventPublisher : IEventPublisher

{

private readonly MyEventSubscriber _subscriber;

public MyEventPublisher(MyEventSubscriber subscriber)

{

LogManager.Log("EventPublisher Started...", LogSeverity.Information);

_subscriber = subscriber;

}

public async Task PublishAsync(IEvent @event)

{

LogManager.Log(

$"Event #{@event.TargetVersion + 1} Published: {@event.GetType().Name} @ {DateTime.Now.ToLongTimeString()}",

LogSeverity.Information);

await Task.Run(() =>;

{

InvokeSubscriber(@event);

}).ConfigureAwait(false);

}

private void InvokeSubscriber<T>(T @event) where T : IEvent

{

var o = _subscriber.GetType().GetMethodsBySig(typeof(Task), null, true, @event.GetType()).First();

o.Invoke(_subscriber, new object[] { @event });

}

}

Then the in-memory subscriber listens to the events and handles them. The class implements IEventHandler for multiple events. You can have multiple subscribers handling the same events pretty easily if you want to. Just do the required code changes to allow the publisher to find them via reflection.

In a production scenario you will publish it to a message broker and the subscribers will get it from there. Message broker approach will give you capabilities like delivery guarantees when required.

public class MyEventSubscriber : IEventHandler<NoteCreatedEvent>,

IEventHandler<NoteTitleChangedEvent>,

IEventHandler<NoteDescriptionChangedEvent>,

IEventHandler<NoteCategoryChangedEvent>

{

private readonly MyReadRepository _repository;

public MyEventSubscriber(MyReadRepository repository)

{

_repository = repository;

}

public async Task HandleEventAsync(NoteCreatedEvent @event)

{

LogEvent(@event);

_repository.AddNote(new NoteReadModel(@event.AggregateId, @event.CreatedTime, @event.Title, @event.Desc, @event.Cat));

}

public async Task HandleEventAsync(NoteTitleChangedEvent @event)

{

LogEvent(@event);

var note = _repository.GetNote(@event.AggregateId);

note.CurrentVersion = @event.TargetVersion + 1;

note.Title = @event.Title;

_repository.SaveNote(note);

}

//See github repo for full source code

There is a very simple read model in the example.

public class NoteReadModel

{

public Guid Id { get; private set; }

public int CurrentVersion { get; set; }

public DateTime CreatedDate { get; set; }

public string Title { get; set; }

public string Description { get; set; }

public string Category { get; set; }

public NoteReadModel(Guid id, DateTime createdDate, string title, string description, string category)

{

Id = id;

CreatedDate = createdDate;

Title = title;

Description = description;

Category = category;

}

}

Finally the read model has its own repository to allow consuming pages/widgets to access it. This is optional.

public class MyReadRepository

{

private readonly MyInMemoryReadModelStorage _storage;

public MyReadRepository(MyInMemoryReadModelStorage storage)

{

_storage = storage;

}

public void AddNote(NoteReadModel note)

{

_storage.AddOrUpdate(note);

}

public void SaveNote(NoteReadModel note)

{

_storage.AddOrUpdate(note);

}

The read models are persisted to a file in this example but you can use any form of persistence that best suits your needs. I recommend a NOSQL document store as most read models will end up being queried by their ID. You can use a relational model if you intend to have some more querying abilities. Do as you see fit.

public class MyInMemoryReadModelStorage

{

private readonly string _memoryDumpFile;

private readonly List<NoteReadModel> _allNotes = new List<NoteReadModel>();

public MyInMemoryReadModelStorage(string memoryDumpFile)

{

_memoryDumpFile = memoryDumpFile;

if (File.Exists(_memoryDumpFile))

{

_allNotes = SerializerHelper.LoadListFromFile<NoteReadModel>(_memoryDumpFile);

}

}

public void AddOrUpdate(NoteReadModel note)

{

if (_allNotes.Any(o => o.Id == note.Id))

{

_allNotes.Remove(_allNotes.Single((o => o.Id == note.Id)));

_allNotes.Add(note);

}

else

{

_allNotes.Add(note);

}

SerializerHelper.SaveListToFile<NoteReadModel>(_memoryDumpFile, _allNotes);

}

public NoteReadModel GetByID(Guid Id)

{

return _allNotes.FirstOrDefault(o => o.Id == Id);

}

public IEnumerable<NoteReadModel> GetAll()

{

return _allNotes.ToList();

}

}

Run the example (Full source code is at https://github.com/dasiths/NEventLite_Legacy/tree/master/src/Examples/NEventLite%20Example)

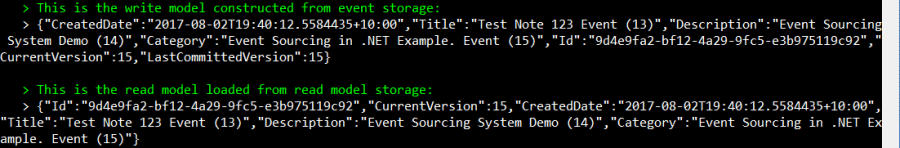

You should see something like this confirming that real model and one constructed using replaying events have the same info.

Wrapping Up

In this series we looked at Event Sourcing with Command Query Responsibility Segregation in depth and looked at an example of how to implement it using NEventLite. For further reading and learning I suggest following Greg Young’s blog and the CQRS google group.

Thanks for reading and please leave your comments and feedback below.

Leave a comment