Event Sourcing Examined Part 2 Of 3

In this 3 part series we will look at what event sourcing is and why enterprise software for many established industries use this pattern.

Index

- Part One

- Introduction to Event Sourcing

- Why Use Event Sourcing?

- Some Common Pitfalls

- Part Two (This one)

- Getting Familiar With Aggregates

- Event Sourcing Workflow

- Commands

- Domain Event

- Internal Event Handler

- Repository

- Storage & Snapshots

- Event Publisher

- Part Three

- CQRS

- Read Side of CQRS

- Using NEventLite

In the last post we looked at what Event Sourcing (ES) with Command Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS) is and discussed some benefits and pitfalls. We also established that ES + CQRS is used for business components within a bounded context. Keep this in mind as we progress towards more technical aspects these patterns.

Getting Familiar With Aggregates

An aggregate is one of the building blocks of Domain Driven Design. Simply put an aggregate is a collection of domain objects that can be grouped into one unit. It is different from a collection (Array, List, Map) because aggregates are domain concepts.

A good example is a purchase order. The purchase order has the order document, collection of order line items and may also have value objects for totals and tax. All of these can be grouped into one unit. This unit is an aggregate.

The purchase order document in this example is the Aggregate Root. The aggregate root is the element which is visible to other contexts. The aggregate root also ensures the integrity of the entire aggregate. All changes or references to the aggregate must happen via the aggregate root and this ensures a natural transactional boundary.

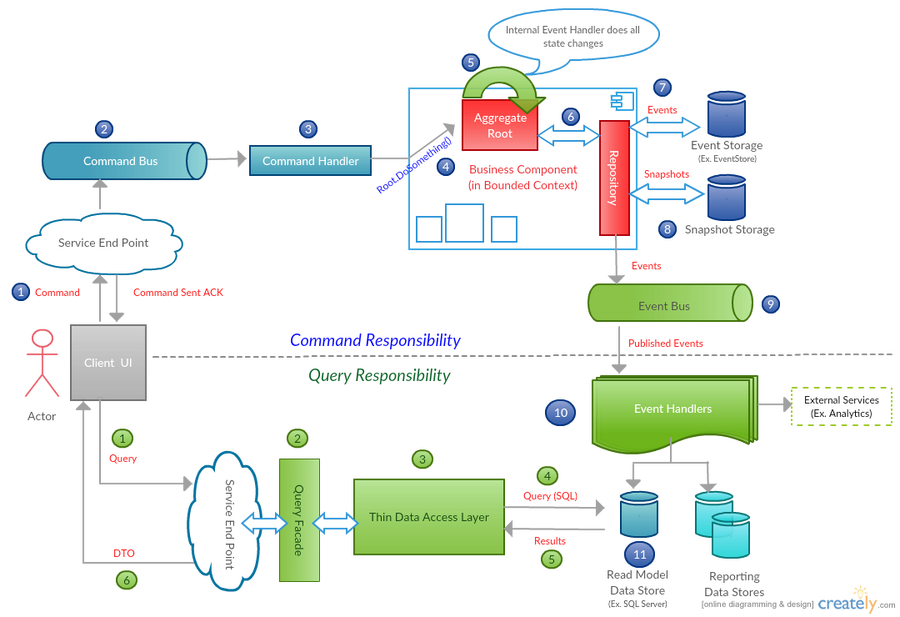

Event Sourcing Workflow (with CQRS)

-

Commands are instructions to do something and are in ”imperative form”

-

Some possible commands are *CreateOrder, AddOrderItem, UpdateShippingAddress, AcceptOrder, ConvertToInvoice etc.

-

Event are in past tense. They indicate an action that happened in the system which results in a state change. OrderCreated, OrderCourierMethodPicked, OrderShippingAddressUpdated etc.

-

The execution of a command can result in many events.

Now let’s walk through the steps. We will take the example of adding a new item to an existing purchase order.

(1) User selects an item “ItemABC” with a Quantity of “X” from inventory and add it to an existing order “OrderXYZ”. It will also have a version number “N” to indicate the version of the current Order. The UI sends this information to a web service. For Example WebServiceProxy.AddItemToOrder(Order, Item, Qty, OrderVersion)

The web service then creates a AddOrderItemCommand with the information received and puts that in a Command Bus (Message Queue). The web service then returns an ack saying the command was forwarded.

This doesn’t always mean the command will be processed or successful. The service can reject it or it can fail. Even when the command is successful, there is no guarantee the read model will be updated “immediately” (remember eventual consistency?). So the UI will have to periodically check the read model to see if it was updated (See if the Order version is now >= N+1) or have a method to listen to the resulting events. There are many ways of handling it. Handling errors is also another big topic by itself.

(2) The command bus’s purpose is to decouple the command creating service from the Command Consumers. The command bus will handle the delivery responsibility.

(3) The command handler registers its interest in the AddOrderItemCommand with the command bus (subscribes).

So the command bus knows to inform the handler when it receives that particular command. It’s important to note that there can only be one command handler per command. This ensures commands don’t get double handled. Technically you can have many handlers but the command should only be “handled” once. This is where idempotent command design comes handy. It’s out of scope for this post but have a read of this article for more information if you’re interested.

(4) The command handler will then load an instance of the AggregateRoot using the unique ID. In this case our order # “OrderXYZ”.

The command handler will now check to see the if version of the aggregate matches the version of the command. This is to check for concurrency and to make sure our command gets executed against the right version of the aggregate. Once this is done, the command handler calls the appropriate method in the aggregate to do the operation and passes the information. For example. PurchaseOrderAggregate.AddItem(Item, Qty).

Hint: A command must only affect one Aggregate as a command that changes multiple aggregates is an anti pattern.

This is where is gets interesting. The AddItem() method doesn’t directly update the state.

(5) We treat state change as a first class concept. To facilitate this we use the concept of “Domain Events” which are immutable records of state change.

-

So to capture state change, the AddItem() method will create an event and Apply it to itself (ApplyChange(@event, true)). The event is the catalyst for state change. In our example the AddItem() method will create an event (OrderItemAdded) and apply it.

-

The Applying of the event will call the “Internal Event Handler” of the Order (AggregateRoot) which in turn will update the state

-

It will also add the event which triggered the state change to a “Uncommitted Changes” collection. This is how the source code might look. NEventLite full source code for AggregateRoot is here. An example is here.

public void AddItem(Guid ItemID, int Qty) {

//Crate the event and call the internal event handler.

//Important: No state changes are done here.

//We also put the current version of the aggregate in the event for consistency

var @event = new OrderItemAddedEvent(this.OrderID, CurrentVersion, ItemID, Qty)

ApplyChange(@event, true);

}

public void ApplyChange(IEvent @event, bool isNew) {

//Call the right Apply method for this event

this.AsDynamic().Apply(@event);

//Only add new events to the uncommitted changes collection

if (isNew) {

UncommittedChanges.Add(@event);

}

}

//This is the "InternalEventHandler"

public void Apply(OrderItemAddedEvent @event) {

//Do state changes here like updating Total and Tax.

//Also do the tasks required to add the order item.

}

The reason we use the internal event handler is to ensure the event gets applied using the same ApplyChange() method when we load (replay) events from storage. It ensures consistency when changing state. (We call ApplyChange() with isNew set to False when we load past events, So it won’t register as an uncommitted event.)

So remember, all state changes must happen inside an internal event handler.

(6) The repository handles the saving and loading of an AggregateRoot. Here is an example of a simple repository interface for an AggregateRoot.

public interface IRepository {

T GetById<T>(Guid id) where T : AggregateRoot;

void Save<T>(T aggregate) where T : AggregateRoot;

}

(7) The events get stored in an “Event Storage”. This can be a relational database or an dedicated event storage engine like EventStore.

(8) As you would have already noticed we have to load events for an AggregateRoot to reconstitute (load) it. To help make this faster we can save “snapshots” every N number of events.

Rather than loading all the events from history to construct an aggregate, we load the last snapshot, and ONLY apply events that are newer than the snapshot. We use our version property saved within the event to identify event sequence number.

The code for saving and loading aggregates will look something like this. (See how the Repository is implemented here for a comprehensive example).

//In our repository implementation

public virtual T GetById<T>(Guid id) where T : AggregateRoot

{

T item;

snapshot = SnapshotStorageProvider.GetSnapshot(typeof(T), id);

if (snapshot != null)

{

item = new T();

//Apply snapshot. this updates the aggregate state to the snapshot version

item.ApplySnapshot(snapshot);

//load events from snapshot version to max

var events = EventStorageProvider.GetEvents(

typeof(T), id, snapshot.Version + 1, int.MaxValue);

//"replay" events

item.LoadsFromHistory(events);

}

else

{

//load events from 0 to max. Basically all events.

var events = (EventStorageProvider.GetEvents(

typeof(T), id, 0, int.MaxValue)).ToList();

item = new T();

//"replay" events

item.LoadsFromHistory(events);

}

return item;

}

public virtual void Save<T>(T aggregate) where T : AggregateRoot {

if (aggregate.HasUncommittedChanges())

{

//Every N events we save a snapshot

if (aggregate.CurrentVersion - aggregate.LastSnapshotVersion >=

SnapshotStorageProvider.SnapshotFrequency)

{

SnapshotStorageProvider.SaveSnapshot(aggregate.TakeSnapshot());

}

//Save events to event storage and publish to event bus. See step 9

....

(9) When we save those events in the Save(T aggregate) we also publish those events to an event bus / event publisher, which can be a message queue.

...

//After saving snapshots in step 8

//Commit Changes to EventStorage

CommitChanges(aggregate);

//Publish to event publisher asynchronously

foreach (var e in changesToCommit)

{

EventPublisher.Publish(e);

}

}

}

Technically this is where the command side of CQRS ends but let’s look at couple more things that need to happen for the cycle to complete.

(10) There will be event handlers that listen to the OrderItemAddedEvent. Those event handlers express their interest in the types of events they want from the event bus (by subscribing).

The purpose of these event handlers are to listen to certain types of events and update the Read Model of our Order. Because we can have multiple event handlers for one type of event (unlike commands) we can have any number of read models for the Order. For example we can even have one dedicated for updating customer order total in a reporting database and another for product totals.

You can probably see the advantages of this now. Our write model (event stream) is totally separate from our read model. This allows us to scale different parts of our system as we wish.

(11) We typically use a in memory database like Redis or a relational database to store our read models. The idea is that the read side our application can quickly load a model by using a simple where clause without having to join anything.

A typical CQRS setup will have a read model for each view. An event handler for each view will listen to events (OrderItemAdded, OrderItemRemoved, OrderItemQtyUpdated) and update the view.

So to catch up.

- We sent a command to add a new item to the order.

- The AggregateRoot created an event(s) to capture the state change. (Even though in our example we only created one event, there can be many events that get generated for a single command)

- The AggregateRoot applied the event(s) to itself to do the state change.

- The repository saved the changes to event storage. (And snapshot as needed)

- The saving of the event(s) also published them to the event bus.

- Event handlers listening to the event received it and updated their “world views” (read models)

What’s Next

That was a very brief explanation of what each step does and how you could go about implementing it. I’ve used very simple code examples. For working examples I highly recommend you have a look at my Event Sourcing library NEventLite at GitHub.

Now that we have looked at the steps in the Command Side of CQRS the next step is to implement the read side. In the next post of the series we will look at how this can be done. I’ll also demonstrate how to quickly get an ES + CQRS application up and running using NEventLite.

I hope this helps you understand how CQRS works. If you have any questions or suggestions please post them here.

Wish you a happy new year and see you soon.

Leave a comment